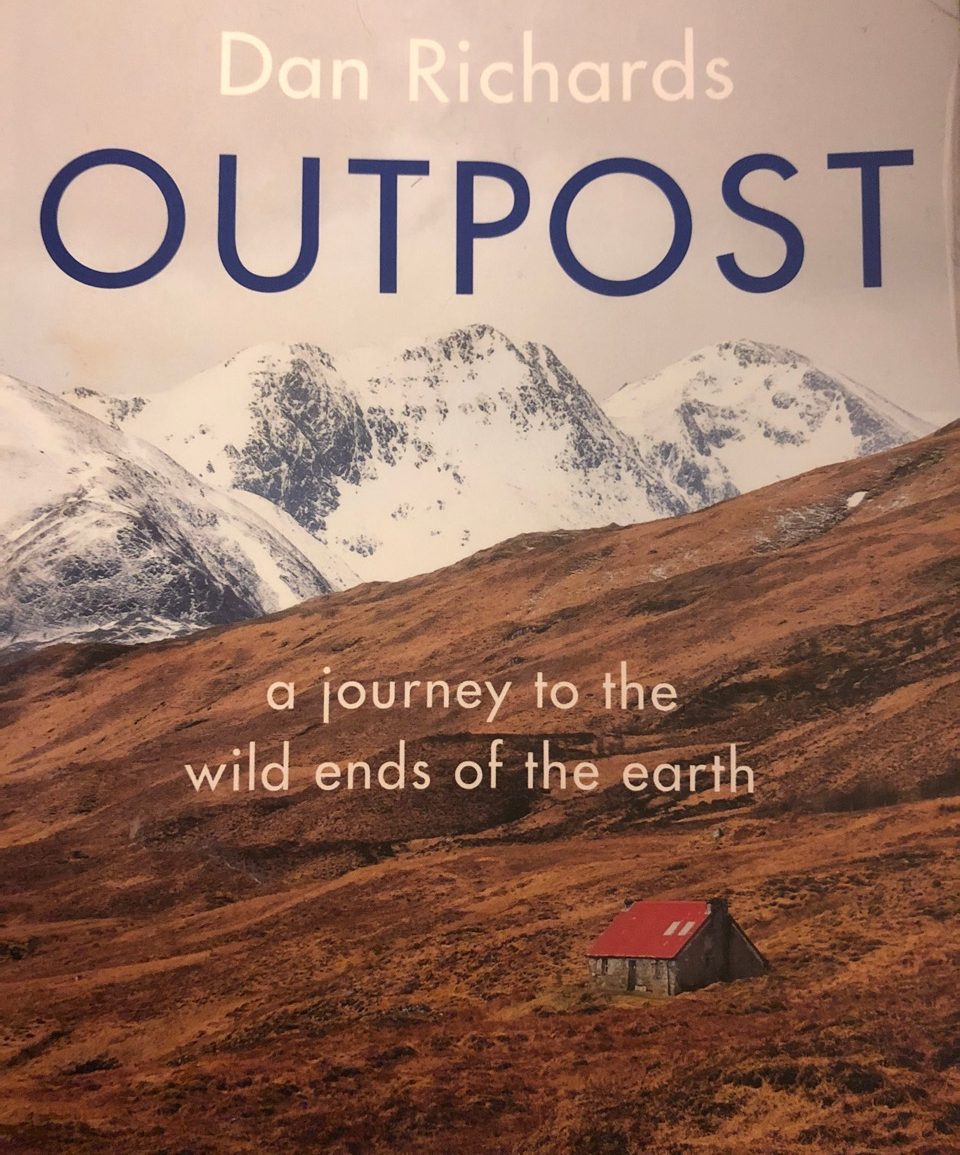

Review: Outpost by Dan Richards

This book captured my attention with its lofty goal: to “explore the appeal of far-flung outposts in mountains, tundras, forests, oceans and deserts.” In my continued state of quarantine living, the thought of an outpost sounded magical. If only I could have departed New York City like many of its wealthier inhabitants when Coronavirus struck. After six months, however, I am still here, a survivor (for now) of a pandemic that has ravaged the city and of protests that at times descended into looting and violence. Amidst it all, I could only dream of outposts and other far-flung abodes. My expectations were high that the author of Outpost, Dan Richards, would transport me to these idyllic oases of peace and solitude, and help answer why people would be drawn to them in the first place.

Unfortunately, by the end of the book I was left with little perspective. Richards had asked numerous questions, but rarely delved deep into the appeal of living, for example, in a fire-watch lookout in Washington State or in a lighthouse off the coast of France. He rarely ascribed meaning and value to the outposts he explored. The inverse was similar. I was often left wondering about the challenges of living or briefly residing in some of these rugged, and probably treacherous, environments. I hoped to gain this perspective from the book, but was disappointed in the end.

A recent New Yorker article about an adventure for Musk Oxen fur provided far more insight and intrigue about living and surviving in outposts and other far-flung places. Wait for the article’s conclusion to discover what happens to the author’s fur. The article did a great job at giving perspective, detailing not only what the author endured in the Alaskan frontier, but what the local human and animal populations experience.

This is not to say that Outpost was boring or mundane. On the contrary, the book brought me – the reader – to places I had never read or heard about previously, such as Svalbard, a Norweigian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. Richards’ descriptions of Ny-Ålesund, a city in Svalbard that is the world’s northernmost civilian settlement, were touching at times, particularly given his connection to the city through his father. Yet it mostly lacked depth. Had Richards latched onto the connection and meaning of far-flung outposts like Ny-Ålesund – both to himself personally and to other visitors/inhabitants – it would have made for a far more compelling tale. Instead, he invited readers to imbibe more of a Yelp review or travel diary than a critical assessment of what draws humans to remote outposts.

Richards’ anecdotes at Ny-Ålesund about polar bears were moving and highlighted the perils of climate change, especially for that species. He did not carry that perspective through, however, to the other remote destinations he explored. Many of these places, from Sæluhús to bothies in Scotland, could all face the detrimental effects of climate change. I know the book was not intended as an environmental assessment, but the pristine nature of these outpost environments is inextricably linked to a healthy Earth. For instance, is the outpost the problem in these pristine locales, or is it the human carbon-emitting behavior far from them? Climate change was a theme I expected Richards to explore further, but he stopped short, only mentioning it a handful of times.

While I was disappointed most of the time, there were nuggets of gold scattered throughout the book. His take on Hvitarnes, Iceland, for example, was mystifying.

“In Hvitarnes the silence hums whilst turning the rocks over for you. Some places invite you to engage and be changed and some give you no choice at all.”

But it left me begging – tell me more about why Hvitarnes gave you no choice but “to engage and be changed.” The gold dust on these types of quotes often led to an empty mine. The title of the book itself – Outpost – was empty and undefined until page 188 when Richards provided his favorite definition in two parts: (i) “a small military camp or position at some distance from the main army”; and (ii) “a remote part of a country or empire.” Why not define these terms earlier or actively explore what constitutes an “Outpost” throughout the book, from beginning to end?

Another “Outpost” theme I expected more of was its isolation and solitude. “Outposts” seemed perfectly designed for someone to “turn off, tune out, and drop in” to their own world. Yet I can imagine how that isolation could be maddening at times. At Desolation Peak for instance, Richards chased Jack Kerouac’s 63-day sojourn overseeing the fire-watch lookout, but spent more time talking about Kerouac than his own experiences. When the chapter ended, I wished Kerouac, not Richards, had told me how “At night, after dinner, he [Kerouac] took to sitting alone down by the swift swirling Skagit with a bottle of wine, writing in his notebook – ‘drinking to the sizzle of the stars.’”

The closest Richards came to nailing the isolation theme was his description of bothying in Scotland, where he highlighted the benefits of solitude in nature.

“The spartan nature of outdoorsing opens us up to the freedom of the unknown. By pulling out the pin that mounts us to a GPS grid we are better able to experience place, space and time. Without our phones we become better connected. Breaking with the digital puts us more intensely in touch with wild country, allows us to negotiate it on the ground and take responsibility for our position.”

I particularly loved the “Goldilocks Principle” he equated to “Outposts” – the idea that “some destinations need to exist in the right geographic location to excite a visitor’s imagination and fulfill their function – to exist in a bubble far enough away from distraction yet close enough to civilization to be practical.” This equilibrium of isolation only touched the tip of the iceberg, however. I also yearned for a better understanding of how everything else feels in this state – food, music, art, etc. How does this “Outpost” and isolated lifestyle inspire the senses? Richards does mention listening to the likes of Radiohead and Steely Dan while writing in Swiss writing huts, and describes how “meals on icecaps taste better than meals anywhere else to the power of ten”, but I guess I wanted more.

The desire for more at the end of each chapter and ultimately, the book, was difficult to comprehend. Was it fueled by my quarantined lifestyle? Could Richards have explored some of these themes with more breadth and depth? As with most facets of life, the answer is probably somewhere in between, in line with the Goldilocks Principle. Outpost may not heed all readers’ desires, but it was probably unlikely to achieve this fulfillment regardless of its prose. Some experiences are simply required firsthand.

1 Comment

2020 Reflections - PolisPandit · December 24, 2020 at 12:53 pm

[…] the summer of culture wars, protests, and a calming pandemic, life continued. The only travel I did was through books, I had an interesting and somewhat troubling interview at Amazon, and I figured out ways to get […]

Comments are closed.