What To Expect In Xi Jinping’s Third Term

China’s Communist Party conclave recently awarded President Xi Jinping a third term in power. More accurately, Xi awarded it to himself.

A third five-year term as China’s leader breaks with recent precedent where leaders have stepped down after two terms. In 2018, Xi amended China’s constitution to do away with the two term restriction.

With China’s Communist Party Congress filled with Xi’s loyalists, there is little to no threat to his authority. No successor has been named, nor is one readily apparent.

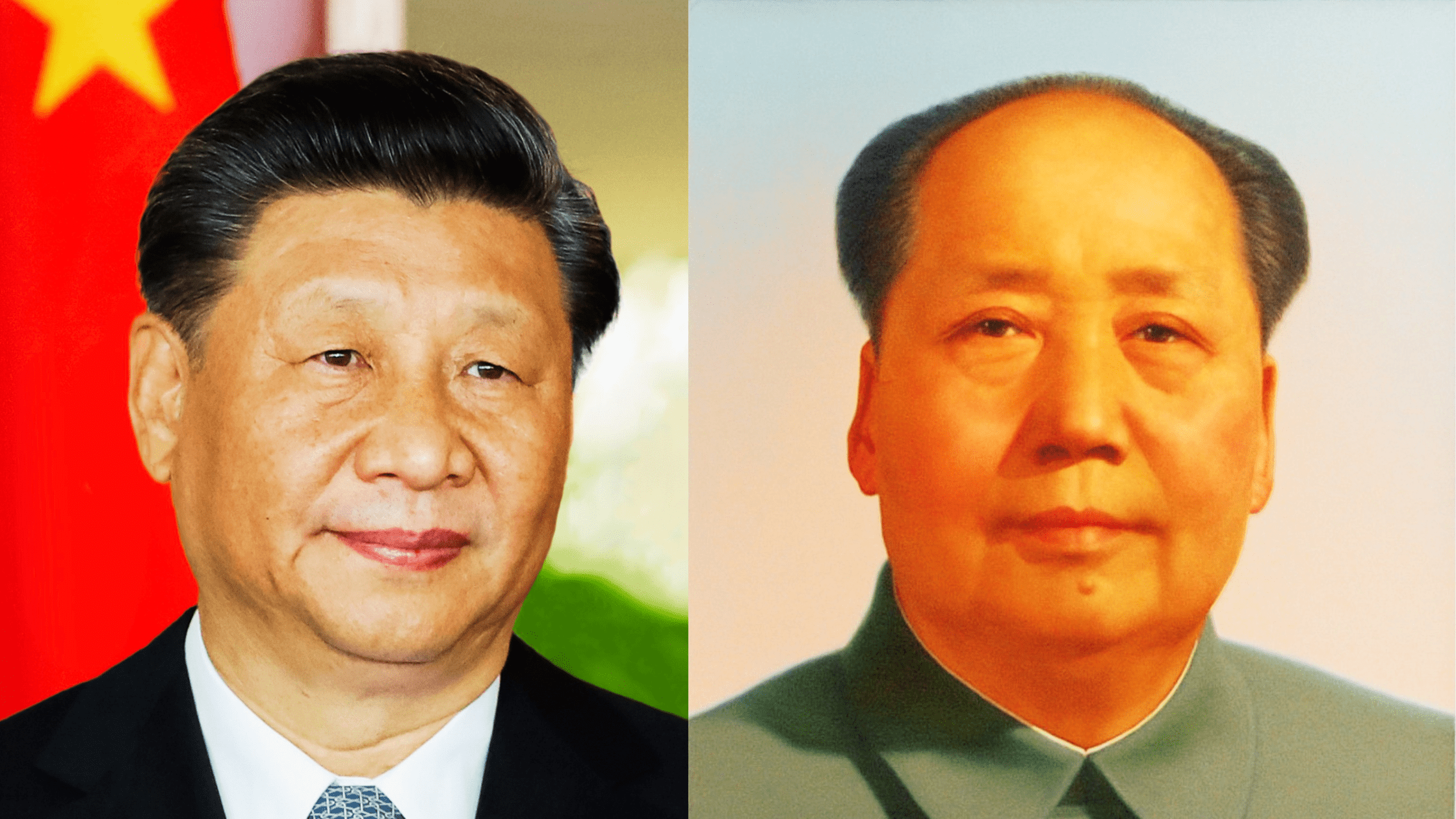

President Xi Jinping cemented and centralized his rule over China in a way not seen since Chairman Mao Zedong. What this likely means for the world is a more aggressive China in global affairs, a shift towards security over economic growth, and more authoritarianism under a more powerful Xi.

Welcome to the era of Mao Zedong 2.0.

An even more aggressive China

Journalists, political scientists, and anyone else interested in Chinese politics typically hang on every word uttered at the conclave. President Xi’s speech laying out the Communist Party’s achievements and vision is particularly telling.

For the past two decades, Chinese leaders preceding Xi have stressed that China was in a “period of important strategic opportunity.” This was generally interpreted to mean that China would focus on economic growth. It meant they weren’t threatened by imminent risks, geopolitical or otherwise.

Previous Chinese leaders, including Xi in the past, have also emphasized that “peace and development remain the themes of the era.” This was generally interpreted to mean that China was confident that the next five years would be peaceful. That there were no clear risks of war or conflict.

Both statements were missing from this year’s conclave. Their overall sentiments were also missing.

It suggests that President Xi might be worried about the future and stability of the Chinese Communist Party. These key omissions potentially indicate that Xi and his party are uncertain about peace, the existing world order, and what upending or destroying that world order might look like. It also reveals a certain level of economic pessimism, which is understandable given China’s recent struggles with its Belt and Road Initiative, property market, and likely upcoming restrictions on American chip imports.

This evident nervousness and uncertainty from President Xi and his Communist Party has led to a significant shift for China.

A shift towards security over economic growth

Instead of continuing to liberalize its economy in favor of state-controlled capitalism, President Xi has made it clear he values control and security over everything else. Notwithstanding the fact that China witnessed probably the most rapid growth of any economy in human history. The country’s embrace of capitalism – even state-controlled capitalism – catapulted it to economic success, lifting millions out of poverty and significantly improving the average Chinese person’s quality of life.

That success has started to slow. American style entrepreneurism doesn’t work in China because the Communist Party would lack control. As we’ve seen in America, oftentimes CEOs wield more power and influence over politicians than vice versa. Or they send their company’s lobbyists to buy political influence.

But China’s interference in the economy has been bad for business in recent years. It doesn’t build confidence for anyone seeking to do business in China when the likes of Alibaba’s Jack Ma suddenly disappear for three months. Or when companies risk censorship or government control should they run afoul of Communist Party preferences and demands.

Could you imagine Amazon’s Jeff Bezos suddenly disappearing in the night because of some arbitrary decision by the American political party in power?

Following President Xi’s consolidation of power at the latest conclave, the markets reacted accordingly. They clearly expect more of this type of economic interference by Xi’s ruling party.

Chinese stocks tanked. The Chinese tech stocks in particular (Alibaba, Tencent, etc.) were affected, dropping by double-digit percentage points. Overall, Chinese stocks finished their worst day (as of October 24th) since the 2008 global financial crisis. The Chinese currency (the Yuan) weakened to a 14-year-low.

Of course it’s not all due to President Xi’s consolidated grip on power and what the markets expect from him. They are also likely pricing in how the world economy will react to a more authoritarian China. One that prioritizes security over economic growth.

The U.S. government is likely to implement and enforce significant export controls on key technology sent to China, especially chip exports (e.g., semiconductors, advanced computing hardware, etc.). This is for a number of reasons, including intellectual property concerns, but regardless, the action would significantly impede China’s technological growth. Especially if other countries like Taiwan play along.

The markets have already reacted accordingly. For most investors, the risks are no longer worth the potential rewards. A more authoritarian China that doesn’t always respect property rights and the rule of law is simply bad for business. Some investors may try to align their investment ethos with President Xi’s priorities, but that’s a dangerous flip of the coin.

President Xi’s consolidation of power has affected the richest people the most. The richest tycoons doing business in China have reportedly lost $12.7 billion in the recent market selloff.

As that continues, and it likely will, China will probably turn harder in the direction of security to counter increasing economic losses and overall stagnation. It will lead to not only a more aggressive China on the geopolitical stage, but a more authoritarian one as well.

An even more authoritarian Xi Jinping

President Xi Jinping has no clear successor. By design. Like other autocrats, including Russia’s Vladimir Putin, potential successors or rivals only threaten to weaken political authority. So autocrats purge the rank and file. Installing loyalists and people who have been there from the beginning.

As we’ve witnessed throughout history, however, this authoritarian strategy has risks. Leadership dominated by one man has a tendency to create major blind spots. Policy missteps and changes in circumstances may not be acknowledged until it’s too late.

Rule by one man is often rigid and inflexible. If economic troubles compound, for example, it could incentivize the expression and exertion of power through other means. As the world has seen in Russia, where Putin’s fledgling economy of perpetual stagflation almost requires war in order to prop itself up.

China and President Xi could become very dangerous on the geopolitical stage if they experience Russian style stagflation for a persistent period.

President Xi might also be incentivized to make misguided policy decisions, as Mao Zedong did with his Great Sparrow Campaign. To a lesser extent, Xi might freeze decision making at lower levels. Many junior party members or businessmen may avoid making decisions for fear of upsetting Beijing or the Communist Party.

All of this amounts to a more authoritarian China under Xi Jinping. A China more in the guise of Mao Zedong than Deng Xiaoping.

Xi Jinping = Mao Zedong 2.0

Like Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping has set himself up as China’s leader for life. His latest construction of the Chinese Communist Party makes clear he has no plans to leave power. He wants to realize an era of stronger, more authoritarian Chinese rule.

Which is why I am calling his third term the start of China under Mao Zedong 2.0. The seeds may have been planted in previous years, but the regime’s new approach is now in full effect, growing like a weed that threatens global democracy’s imperfect garden.

So what to expect in President Xi Jinping’s third term? Less respect for property rights, the rule of law, and human rights. More control over economic activity, censorship, surveillance, and geopolitical aggression.

The world must avoid antagonizing this new version of China. One that is more authoritarian and aggressive. One that doesn’t prioritize the economic growth it prized in the past.

Most importantly, the world must make vividly clear of the consequences that any geopolitical aggression would bring, particularly as it relates to Taiwan. We must learn the lessons of Ukraine, and not miss ample opportunities to deter military adventurism.

I wish I was more optimistic in the success of such deterrence.