Werner Herzog: An Inspiring Guerrilla Filmmaker Who Wrote an Uninspiring Memoir

The barriers to entry for filmmaking have never been lower. Practically anyone can make a movie or video simply by opening the camera app on their phone and using free editing software. As I have studied the craft more and monetized a YouTube channel, one filmmaker in particular kept coming up: Werner Herzog.

He’s probably responsible more than anyone for the guerrilla filmmaking style; a style that translates well to the modern world of YouTube. Herzog is the type of run-and-gun filmmaker who hears reports of a poor peasant refusing to leave a Caribbean island despite an imminent volcanic eruption and arrives two hours later to film it with whatever camera he has.

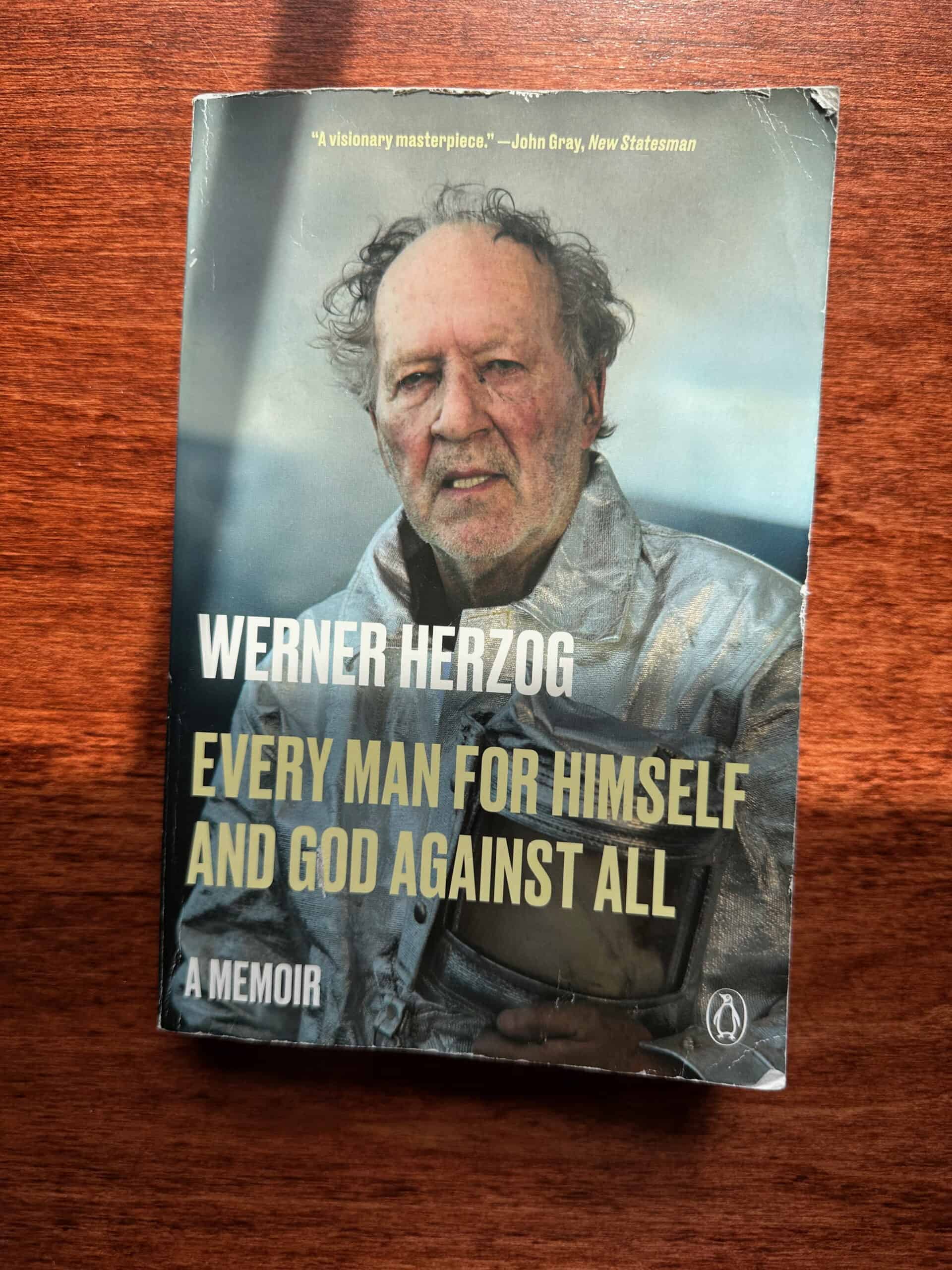

In his memoir, Every Man For Himself and God Against All, Werner Herzog makes it clear that he never thought he would live long. He made films quickly, thinking they may be all that’s left of him. He’s produced, written, and directed more than 70 feature and documentary films (including operas!). And he’s still going.

There is a massive cult following of Herzog, one I didn’t begin to discover until falling down the YouTube rabbit hole of Casey Neistat a few years ago. Both Casey and his brother Van Neistat credit Herzog as a big inspiration. This isn’t surprising because Herzog attracts their type of filmmaker — more of a rogue, rebellious type that is anything but conventional in the Hollywood sense.

While I love the Herzog lore and the one film I’ve seen of his (Aguirre, the Wrath of Gods), his book was surprisingly uninspiring. How could such an interesting, esoteric, and accomplished storyteller make his memoir so disjointed and dull? This was the big question I asked as I struggled through Every Man For Himself and God Against All.

The most interesting man in the world may be Werner Herzog

This guy once tried to walk all around Germany (he was unsuccessful). Herzog grew up in post-war Germany where both of his parents went through de-Nazification, as he describes it. He was a direct beneficiary of the Marshall Plan, fondly remembering care packages he received from America.

The post-war years were adventurous for a young Herzog, but they weren’t easy. He once developed a bad case of croup, and doctors gave him an orange to treat it, the first time he had ever seen one. Herzog remembers being hungry so often that he still cannot throw food away and devours it on sight.

At age 14 he knew he wanted to make films. His knowledge of the industry, however, was severely limited. This forced Herzog, as he describes, “To come up with a cinema of may own.”

In his memoir, Herzog regaled readers with stories of how his more famous films like Fitzcarraldo (a grand opera in the jungle) came to be. He also shared numerous anecdotes from his wild life, from countless injuries like headfirst skiing accidents to sleeping in fields, barns, under bridges, and in random cottages that he broke into (always leaving a note thanking the owners for their hospitality).

At his Rogue Film School, Herzog claims to teach two things — “the forging of documents and the cracking of yale locks.” Yet for all of his fascinating traits and anecdotes, there’s little by way of a cohesive story in his memoir. There’s practically no unifying theme tying everything together.

Disjointed storytelling fails to do Herzog’s story justice

Herzog generally tells his autobiographical story chronologically, but he constantly skips ahead to his films. It’s clear that his films draw inspiration from his life, but the constant back-and-forth between eras is tough to track and often lacks any compelling theme beyond factual information.

We learned that Werner Herzog was inspired to pursue filmmaking at age 14, but there was next to nothing on how he actually got started. For any inspiring filmmaker who treats Herzog as a hero, these are the nuggets of wisdom they seek, but that Herzog fails to provide.

Herzog told us how he stole his first camera, but we didn’t learn the details of how he distributed his first film, let alone how he financed it or provided for himself while operating as a vagabond with a camera.

There is so much left to be desired from his memoir. A good example of this is how he mentioned that nobody under 35 was directing feature films when he was 50+ years ago. But there’s little to no information or context about how he found himself in this class of his own. How did he handle casting, production, and everything else that goes into a feature as a relatively inexperienced young director?

At best, the storytelling is incomplete. At worst, it’s of little value to those who want clear takeaways about Herzog the man, or lessons they can apply to their own pursuit of the filmmaking craft.

We only get peeks at inspiration from Herzog’s memoir

Perhaps this is due to the fact that Herzog has a self-described aversion to “too much introspection or navel-gazing.” He has a great quote on this point, but one that is at odds with writing a great autobiography or memoir.

“If you harshly light ever last corner of a house, the house will be uninhabitable. It’s like that with your soul; if you light it up, shadows and darkness and all, people will become ‘uninhabitable.’ I am convinced that it’s psychoanalysis — along with a few other mistakes — that has made the 20th century so terrible. As far as I’m concerned, the twentieth century, in its entirety, was a mistake.”

It’s hard to write a compelling story about yourself if you don’t harshly light at least part of your soul. The result is otherwise incomplete, revealing only scattershot peeks into an author’s true self.

But some of those peeks into Herzog’s soul are stunning. How the question of truth, for example, has preoccupied him across all of his films (if only that theme had been carried out throughout the memoir). How it takes a poetic imagination to make visible a deeper layer of truth. Herzog summed it up here:

“What the truth is is something none of knows anyway, not even the philosophers or the mathematicians or the pope in Rome. I never see the truth as a fixed star on the horizon but always as an activity, a search, an approximation.”

While Herzog’s memoir may be short on these truths, as we only hear surface-level perspectives, the one film I’ve seen from him was anything but. Aguirre, the Wrath of Gods (1972), explores profound truths that are still relevant today — the corrupting nature of power and ambition, the ills of colonialism and imperialism, and man succumbing to his own madness and delusion.

Unlike his memoir, these themes are consistently applied and brought to a conclusion in Aguirre. Had Herzog done the same in his memoir, it would be required reading for any aspiring filmmaker or anyone interested in the perspective of one of the most “secret mainstream” titans of the industry.

‘Every Man For Himself and God Against All’: an uninspiring read

I probably would have been better off watching more of Herzog’s films than spending a few hours reading his memoir. It was great to learn more about him and understand his life, struggles, and motivations, but these understandings were basic at best and generally not memorable.

The questions of “how” and “why” were often left unanswered. We regularly heard what happened to Herzog throughout his life and his experiences making films, but rarely did we receive the “how” he did something or “why” it was done.

Herzog is concerned that his profession will one day cease to exist. He thinks people have stopped reading or watching feature films, instead relying on tweets, texts, and short videos.

I share his fears, but the best way to counteract that is not by writing a memoir with half-glimpses into the soul of a legendary filmmaker credited with creating a guerrilla, run-and-gun style. If he wants to inspire the next great filmmaker and elevate an artistic medium at risk of extinction in a world of shorter attention spans, we need more deep truths from the man who is always in search of them in his films.

The best way to discover the pursuit of deeper Werner Herzog truths is not from his memoir, but through his films. Maybe it’s unreasonable to have the same high expectations for both.

0 Comments