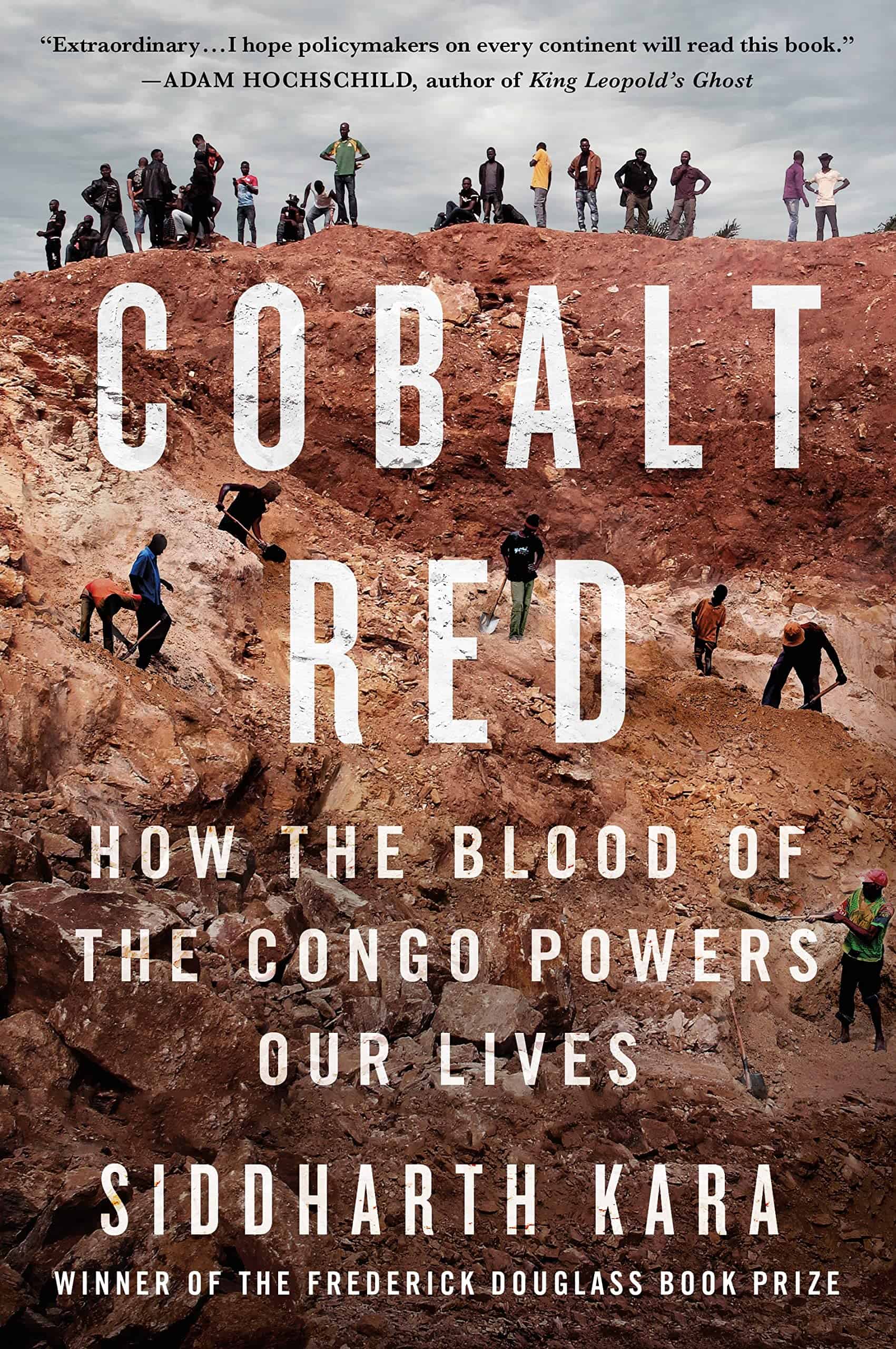

Cobalt Red: The Bloody Truth Behind Congolese Cobalt Mining

Do you own a smartphone? An electric car? If you buy anything with a lithium-ion battery, for which cobalt is an essential element, you’re complicit in the human and environmental destruction caused by cobalt mining in the Congo. Siddharth Kara’s book, Cobalt Red, explains why.

Don’t worry though. I’m guilty as charged too. It’s hard to imagine a world without smartphones.

So many of our 21st-century technologies depend on cobalt for their lithium-ion batteries, and its demand is only projected to increase in the future. Until we find a cobalt alternative, the horrific realities of cobalt mining will likely go unchanged unless significant steps are taken by numerous stakeholders.

The following will review Kara’s firsthand account in Cobalt Red of the devastating truths behind cobalt mining, assess how he allocates blame, and analyze what solutions are available.

The cobalt laundering chain

You may have heard of money laundering – the practice of washing dirty money until it’s “clean.” Not in a washing machine of course, but instead, commingling illegal gains with the cash flow of a legitimate business. For example, the car wash that Walter White operated in Breaking Bad, where he commingled proceeds from his illegal meth business with the legitimate funds of his car wash.

Cobalt laundering works in a similar manner. Many locals in the Congo turn to artisanal – or small-scale – cobalt mining to support themselves and their families. This could involve digging on public lands, an industrial mining site where they’re trespassing, or even in their own backyard.

Artisanal mining is an integral part of the supply chain for cobalt laundering. Depots and other buying houses exist throughout the Congo – which are typically run by Chinese buyers – to purchase this “dirty” cobalt.

Based on Kara’s investigations, the Chinese don’t scrutinize the source of the cobalt. For example, they typically don’t question whether it was mined by child labor or through means of environmental contamination or unsafe labor practices. What the Chinese buyers do, however, is sell this “dirty” cobalt to industrial miners like Glencore who combine it with “clean” cobalt. This is in turn sold to the Apples and Teslas of the world to incorporate into products like the iPhone.

In the process, many Congolese children die through child labor or parental neglect. Many adults turn to artisanal mining to support their families, but then nobody is able to watch the children.

Some of these children are born with birth defects from environmental contamination caused by mining. Those that survive often have high levels of metal in their bodies.

Impressive investigative reporting in the Congo

Kara’s account of the human and environmental toll caused by artisanal cobalt mining is harrowing. He visited numerous Congolese villages over a set period, often going back to follow up with sources and locals who he anecdotally featured in his book. He also visited industrial mining sites themselves but was usually limited in terms of access.

Nevertheless, the investigative steps he details in the book are nothing short of impressive. From official Congolese government sources, to cobalt mining industry groups and artisanal miners themselves, Kara covers the entire industry comprehensively.

The bloody picture Kara paints in Cobalt Red is that of a fake wall between the industrial and artisanal mining sectors. He analogizes it as “trying to determine all the tributaries that feed the Congo River.” And while he unearths significant evidence that industrial miners like Glencore launder cobalt from artisanal miners into their industrially mined “clean” cobalt, they generally shirk responsibility.

Many of these miners point to the depots they purchase from, which give them some degree of cover from the artisanal miners themselves. As a result, industrial miners receive cheaper cobalt that they can make higher margins on when selling to downstream customers like Apple and Tesla, who use it in products bought by you and me.

The Congolese people bear the costs. But how did it get this way?

The Congo’s colonial past: partly to blame, but not entirely

My biggest critique of Kara’s book is the amount of blame he places on the West for this humanitarian and environmental crisis. Yes, Congo’s colonial past set its society back decades. Yes, King Leopold of Belgium was an awful person. But at some point, countries like the Congo need to look inward and figure out how to rectify the situation.

From the notorious Mobutu to the present, Kara blames most of the Congo’s plight on the West and its multinational mining companies like Glencore. Not until the end of the book does he acknowledge that the “voices of the oppressed are the ones who must advance their own cause.”

Sure, he can blame colonial antecedents in law for the current Congolese government empowering itself to sell land to Chinese bidders, but at a certain point, the Congolese people need to hold their government accountable. Nobody is forcing the Congo to transact with the Chinese, selling away valuable rights to their mineral-rich land.

Granted, the Chinese and industrial miners share some of the blame too, but to spend the majority of the book blaming the greed of miners is misplaced. Especially when the Congolese government freely negotiates land rights with these counterparties.

So what’s the solution and does Cobalt Red get it right?

It’s a grave injustice that the very people who dig much of the cobalt don’t get to enjoy its 21st-century riches. Some 70% of the world’s cobalt comes from the Congo, a country with a budget on par with the American state of Idaho, despite having millions of more people.

And what will happen if and when the cobalt runs out? Unlike many countries in the Middle East like Saudia Arabia or the UAE, the Congo has NOT diversified its economy. It has not made its people rich or prosperous from the mineral bounty under their feet.

Some estimate the Congo only has some 40-50 years left of its cobalt dominance. That’s assuming an alternative to cobalt is not developed first. By that point, the millions of Congolese who dug in the dirt with primitive tools or their bare hands will have nothing more to give.

I agree with Kara that the ultimate solution to this horrible problem has to involve all relevant stakeholders. The artisanal miners themselves must be at the table. Organizations that purport to promote sustainable investment in the Congo must actually do their job and check behavior. The Congolese government must protect its people. The people must demand more.

Big corporations like Apple and Tesla who benefit from cheap cobalt should be required to demonstrate in more detail that none of their cobalt comes from child labor or unsafe mines. The Chinese, who are often the ones supplying the cobalt to these larger companies, should be required to do more too.

The entire supply chain is corrupt. They are either willfully blind in a “don’t ask, don’t tell” manner or directly complicit. The artisanal miners must realize the power they can wield over this supply chain. They should be empowered to convene the discussion to get everyone in line.

And how can they get empowered? People like you reading this article and spreading awareness about the problems inherent to cobalt mining. I recommend starting with Siddharth Kara’s book, Cobalt Red. Overall, I would give it four out of five stars.

You won’t look at your smartphone the same way again.

0 Comments